On May 2, Warren Buffett revealed that Berkshire Hathaway bought shares of Amazon as an investment. This is a “spit out your coffee” type moment.

Warren Buffett is, by far, the most renowned and beloved value investor of all time. And Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett’s main investment vehicle since the late 1960s, is the most well-known and revered value investing conglomerate of all time.

Amazon, meanwhile, has a valuation of roughly 80 times trailing 12-month earnings. Based on forward-looking analyst estimates for the year 2020, it is trading around 50 times earnings.

What’s more, Amazon’s future depends on radical expansion and radical innovation — making deep inroads into global markets while stepping up the rollout of cutting edge technologies like cashier-free convenience stores, global cloud storage, automated distribution centers, and even drone deliveries.

To put it simply: Warren Buffett is the ultimate value investor, and Berkshire Hathaway is the ultimate value investing play. Yet Amazon is not only a growth stock, it is a hypergrowth stock.

The TradeSmith research team is long-term bullish on Amazon — more so than on Berkshire Hathaway in fact — for reasons listed here. But that doesn’t change the shock value of Berkshire investing in the most high-profile growth stock on the planet.

In revealing the news to CNBC, Buffett took pains to be clear it was one of the “other guys” who bought Amazon, not him. Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, two internal money managers who are seen as Buffett’s successors on the stock-picking side, each manage around $13 billion worth of Berkshire Hathaway assets.

It was either Todd or Ted who bought AMZN — but it remains astonishing that Buffett let them do it.

During a Q&A session at the annual Berkshire meeting in Omaha, Nebraska, last weekend, Buffett tried to convince his audience of adoring shareholders that Amazon counts as a value investment. He was able to say the following with a straight face:

“The people making the decision on Amazon are absolutely [as] much value investors as I was when I was looking around for all these things selling below working capital years ago. That has not changed… The considerations are identical when you buy Amazon versus… say a bank stock that looks cheap against book value or earnings of some sort.”

If Amazon is a value investment, then the term “value investing” has lost all meaning.

According to Buffett himself, value investing has historically meant buying assets at a discount to their intrinsic value, or otherwise seeking a margin of safety through factors like a stable franchise “moat” and predictable cash flows as far as the eye can see.

Amazon may be a legitimately good long-term investment. But it is not a value investment. There is a reason why growth stocks have a separate category.

While Berkshire’s pivot to buying Amazon is shocking — it is still hard to imagine Buffett green-lighting something at 80 times trailing earnings — it is not the first or even the second time Buffett and Berkshire have made a major pivot.

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s longtime partner, gets credit for the first and most important pivot in Buffett’s investment style many decades ago, when Buffett transitioned from “cigar-butt” style hard-nosed value investing to a search for attractive companies at reasonable valuations.

The original cigar-butt style was aimed at getting one last puff out of an extremely cheap stock (hence the cigar butt metaphor), or capturing the upside from a pile of neglected assets at an extreme discount to net asset value. This could also be considered the antique roadshow approach to investing. Drive around looking for strange odds and ends, hoping to find treasures amid the junk. (In the early days, Buffett used to actually literally drive around in his car, knocking on investors’ doors to ask if they wanted to sell their physical stock certificates.)

In his single greatest contribution to the partnership, Charlie Munger convinced Buffett that such an approach would not scale enough, and that Buffett had to focus more on big, attractive, reasonably priced companies to truly scale over the long term.

With Munger’s help, that philosophical adjustment led to giant purchases of American Express, the Washington Post, Coca-Cola, and other household names that powered Berkshire’s world-beating success over many decades.

Another pivot took place much later, when one of Buffett’s new managers, Todd or Ted, convinced him to take a bullish look at Apple stock, with AAPL eventually becoming Berkshire’s largest holding (and Berkshire Hathaway becoming Apple’s second-largest shareholder).

So, pivots are not entirely new to Berkshire. And in many ways, Berkshire buying a stake in Amazon is an ideal sign of the times. The world is changing dramatically at the margins, and Berkshire is changing with it. This is largely happening because of rapid technological change. By signing on, Berkshire is in effect saying: “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.”

As a sign of how things are changing, consider that the Nasdaq 100 is on track to outperform the broader market for the 10th time in 11 years, according to Bloomberg. Meanwhile the only three companies to have tasted a trillion-dollar market cap are FANG-style tech stocks: Microsoft, Apple and Amazon.

What’s more, Bloomberg now sees “1999-level dominance” in the size of Nasdaq 100 market caps, which now count for about 36% of the S&P 500. Except there is a big difference between now and 1999: The earnings of Nasdaq 100 companies today are four times what they were 20 years ago. The tech giants mostly gush out cash rather than burn it; even Amazon can turn on the spigots when it feels like it.

At the same time, the old guard value investments Berkshire Hathaway used to favor are living in terror of seeing their moats eroded, their brands eclipsed or destroyed, and their long-term edges eaten away by technology-driven competitive change.

As we explained in our Kraft-Heinz write-up, the nature of value investing has changed. That is because the rapid pace of technological advancement is wreaking havoc on the “moats” of old, with traditional value investments too often becoming “value traps.” Berkshire investing in Amazon is direct confirmation of this sea change.

The rapid pace of technological change is also tearing up the economic rulebooks. For example, commentators and economists were recently mystified at a seemingly “impossible” combination: Strong U.S. economic growth, with unemployment numbers at 49-year lows, and yet little to no inflation pick-up.

According to the old rulebooks, if unemployment gets too low, then wage pressures and shortages create inflation. But technology is changing that calculation, and companies like Amazon are at the forefront.

For example, one of the biggest drivers of employment growth over the past 12 months has been warehouses and distribution centers, with nearly 70,000 jobs added. These are e-commerce style jobs, with human pickers working alongside conveyor belts and robots. The mix of human labor and automated process is radically efficient, and the warehouses are growing more automated with each passing day.

In our increasingly tech-driven economy, new jobs are intertwining human labor with automation at a pace that will only accelerate. Think about trucking for example. The truck driver of the future will probably report to a local command center, monitor two dozen or more self-driving trucks at a time, and only take control of a vehicle — through a virtual heads-up display at his station in the command center — in the 5% of situations where the self-driving software has a problem.

Because this “driver” can monitor dozens of trucks at once from one location, he will have the equivalent of a digital desk job, and the total number of humans required to run a trucking fleet will fall by 95% or more.

At the same time, jobs that are falling out of the traditional economy are being replaced by jobs in the “gig” economy — think driving for Uber or Lyft, or delivering food for GrubHub, or logging in to do remote contract work on a per-job basis.

That means unemployment can appear tight because millions of “gig economy” workers don’t show up on the unemployment rolls, even if they are only working 20 or 30 hours a week at the net equivalent of minimum wage. Old jobs paying more are being replaced with new “gig” jobs paying far less (and with no insurance or pension plans).

Last but not least, there is evidence that heavy investments in automation made in the past few years are now starting to add efficiency to corporate bottom lines. This is coming as new technology developments accelerate progress even more, like systems to load and unload trucks with far fewer human workers at a far faster rate.

These factors mean the old assumptions around longstanding presumed relationships — like the one between unemployment and inflation — have to be thrown out.

They also mean that fast-growing technology companies, like Amazon, have the potential to keep growing and finding new efficiencies and sources of profit at a rate and pace nobody could have predicted.

There are many investors waiting for the dominant technology stocks to peter out. “How long can this go on?” the thinking goes. Well, in Nasdaq 100 terms, it has been going on for nearly a decade, and it could stretch out a few years more.

That is because the technology impacts we are seeing today are deep, tidal trends impacting the very nature of productivity and how work is done within the U.S. economy. (Speaking of productivity — U.S. productivity numbers recently hit their highest levels since 2010, another thing you are “never” supposed to see towards the end of a business cycle. That is technology shifting the landscape again.)

We are entering a period of history where “growth” feels intrinsically safer than value because “growth” is about monetizing the future, and in technology terms, the future is kicking down the door.

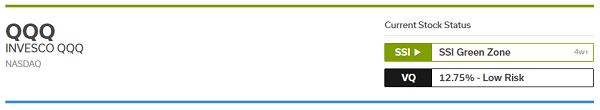

The Nasdaq 100, as represented by QQQ below, remains in the SSI green zone with a 12.75% “low risk” VQ. Allocating to tech stocks on the whole, with a vehicle like QQQ, might be easier on conservative investors’ stomach linings than investing in Amazon at 80 times trailing earnings.

|

Another way to stay ahead in this dynamic and changing landscape — where change is happening so rapidly it can be frightening — is to track the investment ideas of the world’s greatest investors. This is the logic behind our “Billionaires’ Club,” which follows the investment picks of the best investors and money managers in the world.

Without doing a huge amount of research and a deep dive analysis, it is hard to know which companies will thrive in this new landscape and which ones will die. Fortunately, the brilliant minds in our Billionaires’ Club have done this work — and the SEC requires them to report their holdings on a quarterly basis. We analyze those holdings every quarter, filter them for price and trend factors, and share top ideas through our software products, TradeStops and Ideas by TradeSmith.

So, whether or not you join Berkshire by making an Amazon investment, be aware that the landscape really has shifted, thanks to dramatic shifts in the technology landscape that favor the wielders of software code and automation.

Fortunately, there are plenty of things that have stayed the name — factors like human nature, the importance of profit margins and sound business models, the ability of world-class investors (like the ones in our Billionaires’ Club) to stay ahead of the game, and the ability of ordinary investors (like you and me) to navigate markets with investment software.

Founder, TradeSmith |