INVEST LIKE A TRADESMITH

World-Class Investment Tools

Discover hedge fund-level insights designed for the individual investor, like you.

60,000+

Investors on the platform

$30 Billion

Capital invested using our tool

94%

Customer satisfaction across the board

As seen on

Our Products

Designed to help take the emotion out of investing, our data-driven

software turns macro-trends into actionable insights.

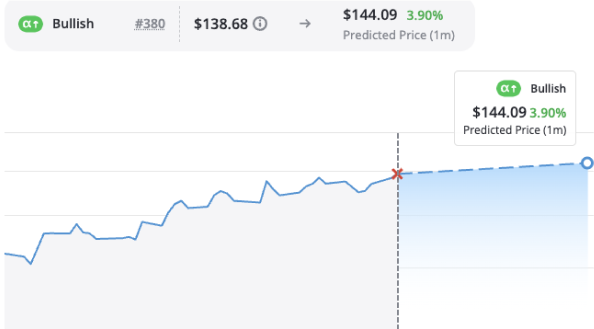

predictive alpha

Access Wall Street-caliber A.I. stock predictions designed specifically for the everyday investor

Predictive Alpha uses TradeSmith’s own A.I.-powered stock prediction system to provide price forecasts on thousands of stocks. These forecasts could enable you to avoid losses and make big monthly gains with a level of certainty that’s rarely — if ever — been achieved before.

See AN-E in action

A.I.-informed stock price predictions at your fingertips.

Industry-leading proprietary A.I. algorithm

Timely & relevant updates and alerts

Curated portfolio of stocks predicted to soar

Automated Buy & Sell Alerts

Our system will take the guesswork out of trading by alerting you when to get in and when to get out of any given stock.

Multi-factor security brokerage sync

Position size calculator for your own portfolios

Asset allocation tool to balance your positions

tradestops

Know precisely when to buy and when to sell.

TradeSmith’s flagship product, TradeStops helps investors effectively and efficiently manage their investments. With powerful risk-based tools, TradeStops is designed to help you invest with risk parity.

Options360

Options-based opportunities without all the hassle.

Use pre-built screeners to find options opportunities based on probability of profit, return on investment, and more. Or build your own custom screener to match any strategy you follow.

95%

Win Rate

+385%

Average Gain

Price Forecast

Get peace of mind by seeing a stock’s volatility, before you ever buy.

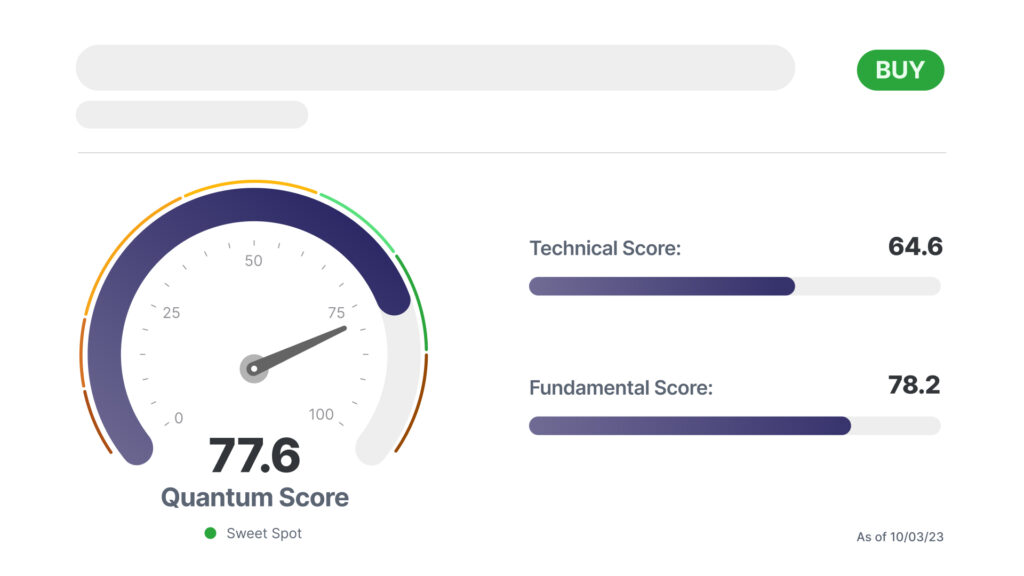

The Quantum Score Adds Up

Jason Bodner’s proprietary system blends a technical and fundamental score to create a total Quantum Score that gives you Jason’s conviction level based on Big Money movement.

Real-time analysis with market shifts

Actionable insights delivered daily

Plug-and-play portfolio tools

quantum edge Pro

Quantitative analysis from an expert you can trust.

Quantum Edge Pro uses quantitative analysis of the best stocks in the market to find the strongest performers – the best of the best – based on fundamental and technical analysis.

Latest Research

Stay up to date with the latests insights and market analysis from our top editors.

This Buy Signal Is Undefeated Since 2008

Listen to this post By Lucas Downey, Contributing Editor, TradeSmith Daily If your portfolio got slammed last week, you’re not alone. The S&P 500 got steamrolled, dropping 3% and easily slicing through one of the most widely followed technical benchmarks: the 50-day moving average. The reason? Most would point to surging...